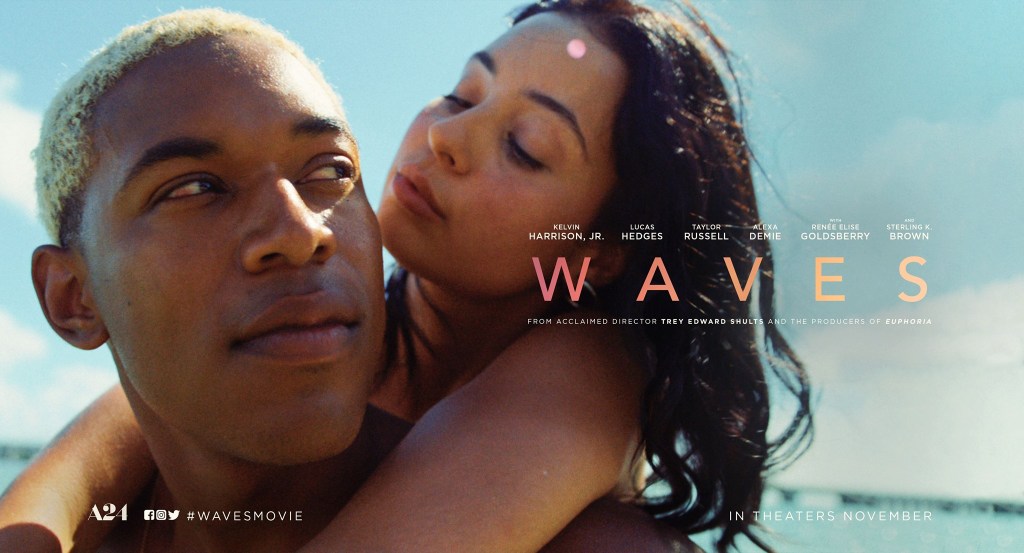

Waves (2019) is a devastating film about a suburban African-American family in South Florida whose seemingly stable life quietly collapses under pressure, silence, and expectation.

Directed by Trey Edward Shults, the film unfolds in two distinct movements, first through the eyes of the son, Tyler, then through his sister, Emily, tracing how one moment of irreversible violence fractures an entire family and forces them to learn how to live with what can’t be undone.

The first half of the film belongs to Tyler. On paper, he’s doing everything right. He’s disciplined. Talented. Strong. A star athlete. A son being molded into the kind of man the world supposedly respects.

And that is exactly what destroys him.

Tyler lives under constant pressure from his father, a man who believes survival comes from control, discipline, and pushing harder, always harder. Feelings aren’t discussed. Pain is dismissed. Vulnerability doesn’t exist. Love is expressed through pressure, through expectation, through an unspoken demand to never break.

So when Tyler’s life starts to unravel, an injury that threatens his future, a relationship that grows complicated, a pregnancy he’s not prepared for, he has nowhere to put the fear, the shame, the grief. He doesn’t know how to feel. Only how to perform.

The pain stays inside. It festers. It rots.

What makes Waves so unsettling is how ordinary this descent feels. There’s no villain. No dramatic betrayal. Just everyday pressure. Everyday silence. Everyday “man up.” Until one night, in a moment of rage and panic, Tyler kills his pregnant girlfriend. I really did not see that coming!

And just like that, his life is over.

Not only because of what he’s done, but because everything he was built to be collapses at once. The future disappears. The identity disappears. The pressure that once felt like purpose becomes unbearable guilt.

Then the film breaks in half into two different perspectives. This is unique as a lot of films tend to stay with one narrative.

The chaos drops out. The noise fades. We shift into the aftermath, into the quiet that comes after something unforgivable has already happened.

The second half of Waves belongs to his sister Emily.

Emily’s half of the film follows what happens after everything has already been ruined. She starts dating. She goes to school. She laughs sometimes. On the surface, life keeps moving, but underneath it all is grief that never leaves the room. Her relationship isn’t dramatic or explosive, it’s quiet, patient, and unexpectedly gentle. Someone sits with her instead of demanding answers. Someone lets her exist without pushing her to be okay.

There’s no moment where she “gets over it.” She just learns how to keep living alongside the loss. How to feel something good again without guilt. How to let closeness back in after devastation.

And that, in itself, feels radical. And that contrast is the point.

The film is saying something painfully simple and deeply uncomfortable: suppression destroys, softness saves.

The filmmaking makes sure you feel this in your body. The first half is overwhelming, dizzying, aggressive. The camera never rests. It spins, presses in too close, destabilizes even ordinary moments.

The soundtrack is loud and relentless, Kanye West, Frank Ocean, Tyler, The Creator, overstimulating, but amazing soundtrack. It’s used not as background music but as emotional pressure. Joy feels frantic. Love feels desperate. Silence is unbearable.

It feels like being trapped inside Tyler’s nervous system.

When the perspective shifts to Emily, everything changes. The music softens. Bon Iver drifts in instead of crashing. The camera steadies. Shots linger. Faces are allowed to exist without being chased. The film finally exhales.

That contrast isn’t stylistic. It’s the message.

And then there’s the setting.

Waves was filmed in South Florida because this is where Trey Edward Shults was living at the time, in Davie, in Broward County, in that very specific 954/305 world. He was filming the place he actually knew, the suburbs, the schools, the long roads, the in-between spaces where real life happens.

You can feel that it’s personal. Not styled. Not romanticized. Just familiar.

And maybe that’s why it hits harder for me, because this is my hometown too.

The car rides with the music too loud. The flat neighborhoods. The beaches. It feels like a love letter, even when it hurts.