Set in the neon-soaked underbelly of Tokyo, the story follows Oscar, a young American drug dealer, and his sister Linda, who works as a stripper. They are emotionally fused by shared childhood trauma and an unspoken promise to never abandon each other.

Early in the film, Oscar smokes DMT, a powerful psychedelic substance known for inducing intense, reality-dissolving experiences. Shortly after, during a police raid in a nightclub bathroom, Oscar is shot and killed.

Or at least… we assume he is.

What follows is the core of the film. The camera detaches from the body and begins to drift, hover, and float through time and space. We move through memories, present moments, and imagined futures, observing Linda and the people around her as if from outside the physical world.

The film suggests that what we’re witnessing may be Oscar’s consciousness after death, his final neural firing, or something in between, a liminal state where identity hasn’t yet dissolved.

Gaspar Noé never confirms whether this is literally the afterlife, a hallucination, or the brain’s last attempt to make meaning as it shuts down. The ambiguity is intentional.

DMT is a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain plants and in trace amounts in the human body. When inhaled, it produces an experience that is often described as:

- Rapid and overwhelming

- Visually intense, with fractal imagery and bright, geometric patterns

- Associated with a loss of ego or personal identity

- Marked by the feeling of “leaving” the body or entering another realm

- Extremely short in duration, yet subjectively timeless

In Enter the Void, DMT isn’t just a substance Oscar uses, it’s a conceptual doorway. Noé uses it as a narrative device to explore what consciousness might experience at the moment of death.

The floating, first-person camera mimics reported DMT experiences: the sense of watching oneself from above, slipping through memories, losing linear time, and existing without a body.

The film implies that Oscar’s death, occurring while DMT is active in his system, blurs the line between a chemical trip and a metaphysical transition. Is this what dying feels like? Or is it simply the mind flooding itself with meaning as it goes dark?

Rather than portraying death as an ending, The film treats it as a perspective shift. The body collapses, but awareness continues, watching, lingering, unable to intervene. Oscar becomes a witness to the consequences of his life, especially the impact of his absence on Linda.

There is no judgment, no heaven or hell, no moral framing. Just observation.

The film draws loosely from ideas found in Tibetan Buddhist thought, particularly the Bardo, a transitional state between death and rebirth. But Noé strips it of spiritual comfort. What remains is something raw and unsettling, consciousness without agency, attachment without a body.

What makes Enter the Void uncomfortable isn’t just the drugs, sex, or violence. It’s the implication that death may not be peaceful or immediate. That awareness might linger. That love, guilt, and desire don’t end when the heart stops.

Whether Oscar is truly dead or trapped in a chemically extended moment of dying is left unresolved. And that uncertainty is the point.

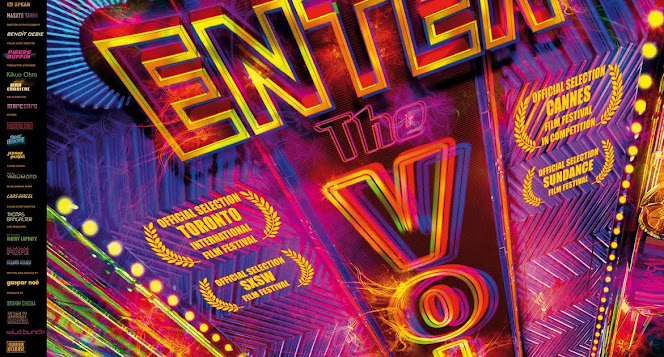

Visually, Enter the Void is overwhelming, intentionally so. The strobing lights, endless neon signage, pulsing club scenes, and hypnotic camera movements create a sensory overload that borders on physically exhausting.

Noé’s camera work is both the film’s greatest strength. The floating, impossible perspectives place the viewer in positions that feel invasive, voyeuristic, and at times deeply uncomfortable.

It is not a film I would recommend lightly, or casually. It demands emotional openness and a willingness to be unsettled. It can trigger anxiety, dissociation, or existential dread in the wrong context. But for viewers drawn to cinema as an experiential art form rather than storytelling alone, Enter the Void is simply unforgettable.